Cover photo by Evan Dennis on Unsplash.

In this article I will give you a deeper insight why we decided to make a major breaking rewrite of the secureCodeBox. First I'll give you an overview of the v1 architecture and the rationale behind. Also outline the problems we stumbled upon using secureCodeBox v1 for some years now. Afterwards I introduce you to the new secureCodeBox v2 architecture and the rationale behind.

Architecture of the Version 1

Let's start with the design goals of v1:

- It should be possible to easily integrate new scanners.

- All components should be loosely coupled to easily swap them.

- The whole deployment should run anywhere (local, VMs, Cloud, etc.) and scale.

- The definition and implementation of a scan process should be easy.

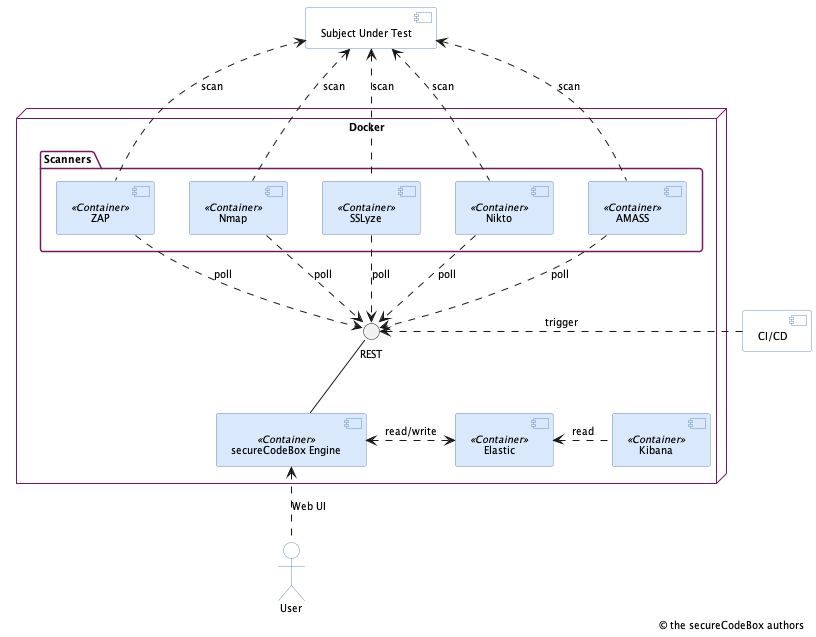

This is not an exhaustive list of requirements for the architecture, but the most important ones. This resulted in a design outlined in the next image:

This is a simplified component diagram of the secureCodeBox v1. Unimportant components (like reverse proxy, vulnerability management system, etc.) are left out for brevity. So lets dig deeper into these goals and how they were achieved.

I introduce some wording for the next sections:

- Scanner: This is the component composed of a container with a particular security scanner.

- Engine: This is the core component responsible for orchestration of scanners, providing the REST API and the web UI in secureCodeBox v1.

- Scan process: A description what kind of scanners we want to run against a target.

So, let's have a look how we tried to achieve the architectural design goals from above.

Easy Integration of New Scanners

There are a lot of tools for security testing out there. Hence, it was necessary to make it possible to integrate them easily. We achieved this by encapsulating each scanner into its own Docker container. The basic idea was: If there is a new scanner, just put it inside a Docker container and attach it to the secureCodeBox engine.

Typically, these scanners are Linux based command line tools and putting them inside a container is the easy part. On the other hand, each of these tools have different user interfaces:

- They use different options, arguments, and config file formats.

- They vary in what they give as result (print to STDOUT or files) and how (XML, JSON, custom etc.).

So obviously we needed some glue code which translates from the secureCodeBox engine to the command line arguments of the scanner and translates back the results to a unified format the engine can handle. This resulted in the scanner scaffolding frameworks (Ruby and NodeJS) to help with the scanner integration.

Loosely Coupling

We didn't want tight coupling between the secureCodeBox components, so we may easily swap one of them without touching everything else. With the approach of putting every scanner in its own container, we did the first step. The second step was a REST API for the communication between engine and the scanners. So we ended in a so-called microservices architecture where each scanner and the engine are services.

At this point we had to choose between two approaches for integrating the scanners with the engine:

- The engine pushes new work to the scanners, or

- the scanners polls the engine for new work.

We decided to choose the second approach because this simplified the implementation tremendously: The engine must not do bookkeeping which scanners are available, crashed or need to be (re-)started. A scanner registers itself at the engine by polling for work and send back the result when finished. But with the consequence that scanners must run all the time to poll the engine and respond itself on crashes.

Deployment and Scaling

This design goal is connected with the first one. As we decided to put each security scanner into its own container, it was not far to seek to put all components into containers and deploy them with Docker Compose. So it was possible to run the secureCodeBox local on your machine, on virtual machines or even in any cloud environment. We ran our first production deployment with an early version of Rancher on a virtual machine. Later we scaled out on multiple VMs and Google Cloud Platform.

Implementation of the Scan Process Workflows

We needed a way to define our typical scan processes. For example such a process may look like:

- Scan for open ports.

- Scan for TLS configuration errors.

- Scan for outdated web servers.

- Someone must review the findings.

Very early we stumbled upon Camunda which is a BPMN engine and we thought: "Our scan processes merely looks like such a business processes." We decided to use Camunda in the engine to manage all the workflows. That saved us a lot of time and effort because implementing such a big configurable state machine is no trivial task. Also we were keen of the UI Camunda brings with it to visualize the BPMN. So we built the engine on top of Spring Boot with Camunda and modeled the scans with BPMN and added a rich web UI.

Problems with This Design

We used secureCodeBox v1 heavily in the last couple of years in various projects and to scan our own infrastructure. While using it we encountered that some of our decisions were not the best ones.

Lot of Repositories to Release

Due to the fact that we decided to use a micro service architecture we wanted to enforce this by separating the components as much as possible to reduce risk of tight coupling. This resulted in a pattern where we use own repositories for each component. This led to the vast number of roundabout a dozen repositories at GitHub. All these repositories needed to be coordinated and aligned for a release which results in a lot of tedious work. Also we now had a lot of different places to look for issues and documenting things.

Scanners Running All the Time

Above I mentioned that we decided to use polling to coordinate the scanners. Firstly it looks reasonable to choose this approach because a push-based such resource handling is hard to implement. But as we used the secureCodeBox more and more in our projects we realized that cloud is not always that cheap as one would expect: If your containers run all the time cost may rise very quickly. In our case we used the secureCodeBox to scan all our company's infrastructure and hence we had hundreds of running scanner containers to spread the load. Due to the fact that they're running all the time and not only when they have work our operational costs rises very quickly. So in retrospective this architectural choice was not that good.

Boilerplateing for Scanner Integration

The integration of new scanners were not that easy as we assumed. First problem was you have to write lot of boilerplate code to translate from the scan task coming from the engine's API – Remember, above I said that a scanner polls for these tasks by requesting an API endpoint of the engine. – into the appropriate format of the scan tool's CLI. Also you needed to write the translation back from the tool's output to the format the engine can deal with. As if this was not enough you also had to write a BPMN process model which describes the scan and makes it possible to integrate it into the BPMN based engine. Turns out: That's too much tedious work. Nobody in the community contributed new scanners. In fact only one of our core committers did this extra mile and contributed new scanners (thanks Robert).

Heavy Engine with SpringBoot and Camunda

We decided to use the Camunda BPMN as core for our engine. We used the ready packaged dependency with Spring Boot because we wanted to provide a REST API for the engine and also add some nice web UI. So, Spring Boot looked like a reasonable choice. But it turned out as a big legacy. First it was a very large code base. If you have ever seen a Java based web application you know what I mean. Of course, Spring Boot reduces a lot of the typical Java boiler plate, but this is also part of the problem: It hides a lot of stuff behind some magic autoconfiguration. If you're not familiar with Spring Boot you have no clue how all this works. This made it very hard for contributors to fix or extend the engine. And as a site note: We discovered that nobody really used the fancy web UI. Frankly, it was only used for convincing business people in meetings.

Conclusion

All these drove us to make a major rewrite of secureCodeBox. How we changed the architecture will be described in a follow up article on this blog.